Roku's Reward

A 2006 film about AR gaming drew 200,000 views. For years, people asked when they could play it. There was no game. Just a vision that landed.

What if your city became a game?

This is where my innovation storytelling work began. In 2005, as CTO at HP, I was tasked with creating a vision film that would showcase emerging augmented and virtual reality technology. The goal wasn't to sell a product—HP's interest was in their back-end telecommunications infrastructure. The goal was to show what that infrastructure could enable.

We made a film about a game that didn't exist. And people wanted to play it so badly they kept asking when it would ship.

The Story

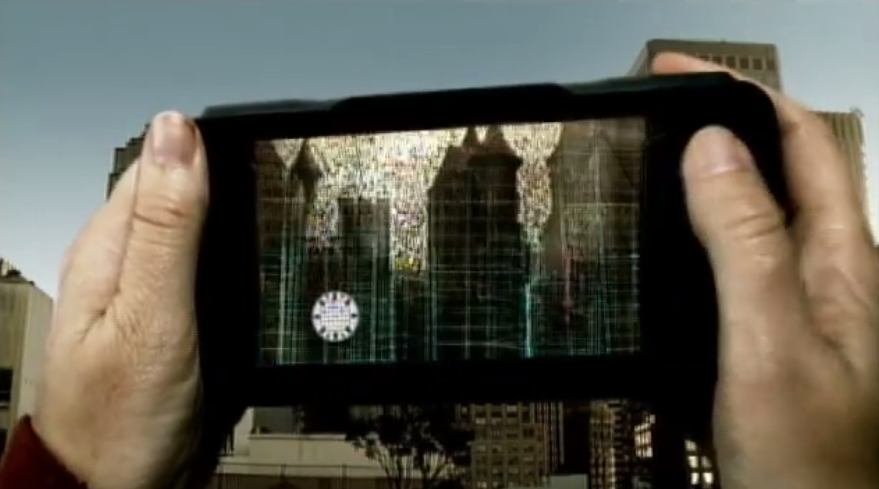

A teenage boy races through the streets of San Francisco, handheld device in hand. But he's not just running through the city—he's running through a game layered on top of it.

He points his device at buildings and landmarks, and digital information appears. Clues. Points. Bonuses. He's competing against other players scattered across the city, all of them navigating the same physical streets while playing in a shared virtual space.

He holds his device up at a historic site and sees a battle scene from the past overlaid on the present. He scans a storefront and unlocks a hidden reward. The whole city has become an interactive playground where physical and digital reality merge.

No one stops to explain augmented reality. He just plays.

Building Something That Didn't Exist

This film required us to invent the game before we could show it.

We had to design the rules. How do you score points? How do you compete with other players? What makes it fun? What makes it feel real? We had to think through game mechanics for a technology category that barely had a name yet.

Then we had to figure out how to film it—how to show a teenager interacting with digital elements that wouldn't exist for years. The production had to sell the experience without any of the actual technology in place.

That constraint—showing a future that hasn't been built—is what makes innovation storytelling different from product marketing. You're not demonstrating features. You're creating belief in a possibility.

What Happened Next

When we posted the film online, it immediately drew over 200,000 views.

But the real signal was in the response. For years afterward, every time I gave a talk, someone would approach me and ask: "When is HP releasing that game? I want to play it."

I'd have to remind them that the film came out in 2006. There was no game. It was a concept video.

They didn't care. The experience felt so real, so inevitable, that they'd already decided they wanted it. The film had done its job—it made people see a future they couldn't unsee.

Before There Was a Word for It

"Roku's Reward" came out in 2006. The iPhone launched in 2007. Pokémon GO launched in 2016.

We were showing location-based AR gaming a decade before it became a global phenomenon. Not because we were predicting the future—because we were trying to help people feel what the future might be like.

That's what innovation storytelling does. It doesn't forecast. It doesn't explain. It lets people step inside a possibility and experience it as if it already exists.

When they walk out of that experience wanting what they saw, you've done something no whitepaper or product roadmap ever could.

The Beginning of a Practice

This film taught me something I've carried through every project since: when innovation stories work, people stop seeing them as fiction.

They start expecting them as reality.

That response—the gap between "that's interesting" and "when can I have it"—is the measure of whether an innovation story has landed. "Roku's Reward" was the first time I saw that gap close completely. It wouldn't be the last.

Client: HP

Year: 2006

Capability: Innovation Storytelling