How to Stop Overthinking Your Decisions

Gathering more information feels responsible. There's a point where it tips into overthinking and keeps you stuck.

You've got a decision you've been putting off. Maybe it's a career move. An investment. A difficult conversation you keep rehearsing in your head but never starting.

You tell yourself you need more information. More data. More time to think.

But you're not gathering information. You're hiding behind it. What looks like due diligence is actually overthinking in disguise.

The certainty you're waiting for doesn't exist. It won't exist until after you decide and see what happens.

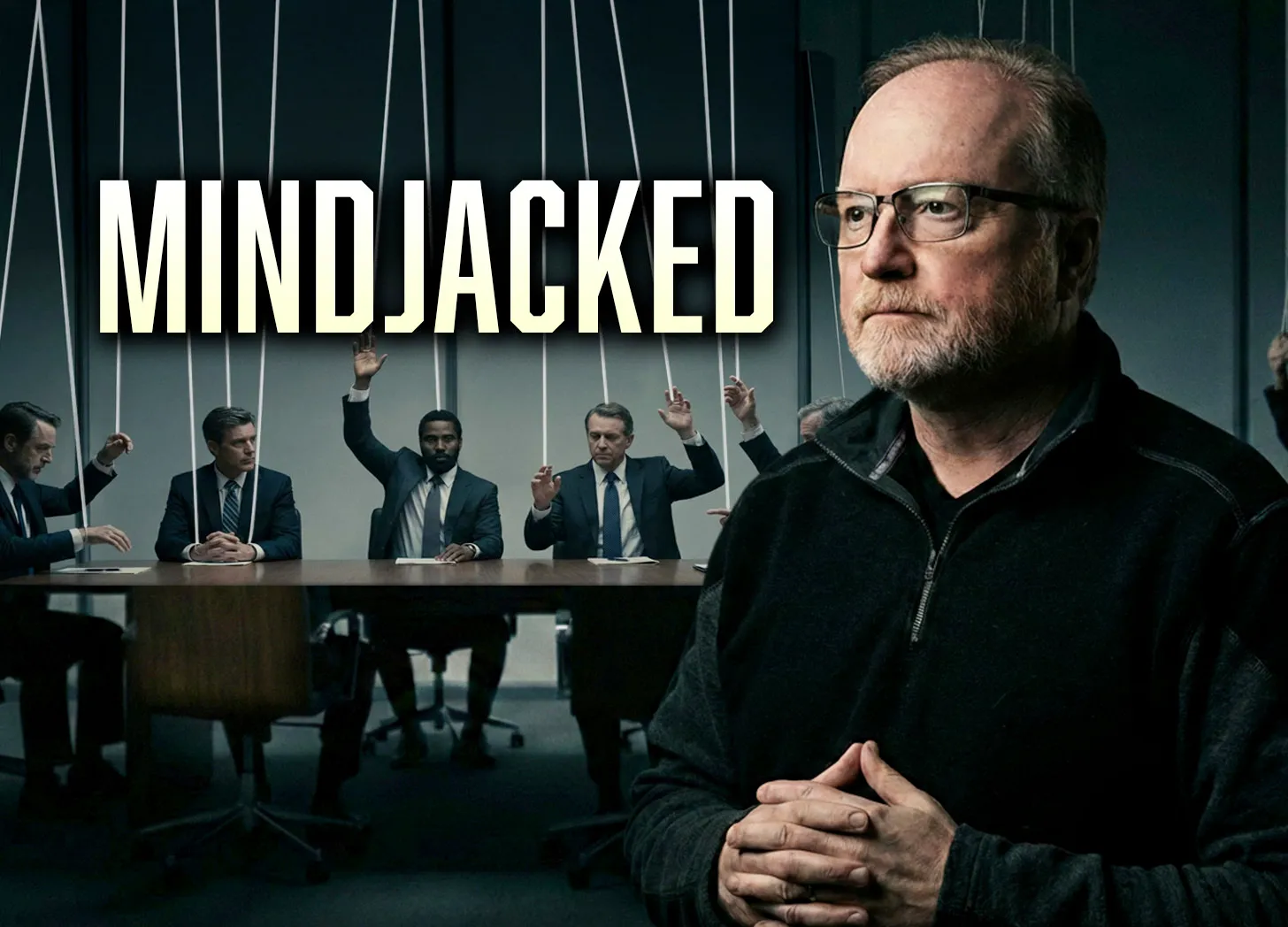

I call this mindjacking: when something hijacks your ability to think for yourself. Sometimes it's external. Algorithms, experts, crowds thinking for you. But sometimes you're the one doing it. That endless research? It feels like diligence. It functions as delay. You're not being thorough. You're mindjacking yourself.

Today, you'll learn a framework for knowing when you have enough information, even when it doesn't feel like enough. Because deciding before you're ready isn't recklessness. It's a skill. And for most people, that skill has completely atrophied.

... or listen to the podcast.

The Real Cost of Waiting

At a California supermarket, researchers set up a tasting booth for gourmet jams. Some days, the display showed 24 varieties. Other days, just six.

The bigger display attracted more attention. Sixty percent of people stopped to look. But only three percent actually bought jam. When shoppers saw just six options? Thirty percent purchased. Ten times the conversion rate.

More options didn't help people choose. More options paralyzed them. The jam study has been replicated across dozens of categories since then. The pattern holds. More choices, more overthinking, fewer decisions.

Think about your postponed decision. How many options are you juggling? How many articles have you read? Every expert you consult, every scenario you play out in your head... you're not getting closer to certainty. You're adding jams to the display.

And while you're researching, the world keeps moving. Opportunities close. Competitors act. Your own situation shifts. The decision you're avoiding today won't even be the same decision six months from now.

Waiting has a cost. Most people dramatically underestimate it.

The Two-Door Framework

So how do you know when you have enough information?

Jeff Bezos uses a mental model that's useful here. Picture every decision as a door you're about to walk through. Some doors are one-way: once you're through, you can't come back. Selling your company. Getting married. Signing a ten-year lease. These deserve serious deliberation.

Most decisions, though, are two-way doors. You walk through, look around, and if you don't like what you see, you walk back out. Starting a side project. Trying a new marketing strategy. Having that difficult conversation. The consequences are real, but they're not permanent.

The mistake most people make is treating two-way doors like one-way doors. They apply the same level of analysis to choosing project management software as acquiring a company. They're not being thorough. They're overthinking reversible choices.

That's how organizations grind to a halt. That's how careers stall. That's how opportunities evaporate while you're still "thinking about it."

Before you gather more information, ask yourself: Can I reverse this? If yes, even if reversing would be annoying, you're probably overthinking it.

The 40-70 Rule

General Colin Powell used a decision framework he called the 40-70 rule. Military leaders and executives have adopted it for decades.

The Floor: 40%

Never decide with less than forty percent of the information you'd want. Below that threshold, you're not being decisive. You're gambling.

The Ceiling: 70%

Don't wait for more than seventy percent. By the time you've gathered that much data, the window has usually closed. Someone else acted. The situation changed. The decision got made for you, by default.

The Sweet Spot

That range between forty and seventy percent is where good decisions actually happen. It feels uncomfortable because you're not certain. That discomfort isn't a warning sign, though. It's the signal that you're doing it right.

Most overthinking happens above seventy percent. You already have what you need. You're just not ready to commit.

If deciding feels completely comfortable, you've probably waited too long.

The Productive Discomfort Test

"I genuinely need more information" and "I'm using research as a hiding place" feel identical from the inside. Both feel responsible. Both feel like due diligence.

I once watched a friend spend eleven months researching a career change. She read books. Took assessments. Talked to people in the field. Built spreadsheets comparing options. She knew more about the industry than people working in it. And at month eleven, she was no closer to a decision than at month one. The research had become the activity. The feeling of progress without the risk of commitment.

She wasn't preparing. She was hiding. And she couldn't tell the difference.

So how do you tell productive research apart from overthinking? Four tests:

Test 1: The Flip Question

Ask yourself: What specifically would change my decision? Not what would make me more comfortable. What would actually flip my choice? If you can't name something concrete, you're not gathering information. You're stalling.

Test 2: The Repetition Check

Are you learning genuinely new things? Or finding different sources that confirm what you already suspected? The third article about the same topic isn't research. It's reassurance-seeking dressed up as diligence.

Test 3: The Timeline Test

Have you set a deadline for deciding? "When I have enough information" isn't a deadline. That's an escape hatch that never closes. A real deadline has a date. It's in your calendar. It arrives whether you're ready or not.

Test 4: The Broken Record Test

If you keep telling the same people "I'm still thinking about it" for the same decision over weeks or months, that's not thinking. That's avoidance on autopilot. You've become a broken record, and everyone can hear it except you.

Here's the uncomfortable truth: if you fail more than one of these tests, you probably already have enough information. You're not under-informed. You're over-attached to the comfort of not having decided yet.

The goal isn't to eliminate uncertainty. You can't. The goal is to act while uncertainty is still manageable, while you can still correct course, while the opportunity is still breathing.

Your Decision Deadline

That decision you've been postponing? It has an expiration date. Not one you set. One that's already running.

Every week you wait, the context shifts. The opportunity narrows. The person you'd need to have that conversation with forms new assumptions about your silence. You're not preserving your options by waiting. You're watching them quietly disappear.

This week, not someday, identify the decision you've been postponing. The one that popped into your head when this video started. You know exactly which one I mean.

Set a deadline. Pick a specific date by which you will decide. Not a date by which you'll have complete information. A date by which you'll commit to a direction. Write it down. Put it in your calendar. Make it real.

Then ask the two-door question: Is this reversible? If it is, your deadline should be soon. Days, not months.

When that deadline arrives, decide. Not perfectly. Not with complete confidence. Deliberately, with the information you have, knowing you can adjust as you learn more.

And once you've decided, set a checkpoint. Pick a date, two weeks out, a month out, when you'll evaluate whether to stay the course or walk back through the door. This isn't second-guessing. It's building the feedback loop that makes two-way doors work. Decide now, verify later.

That feeling of deciding before you're fully ready? Get used to it. That's what good decision-making actually feels like.

Conclusion

Uncertainty isn't going away. Not for this decision, not for any decision that actually matters. The question is whether you'll learn to act within it, or let it become a permanent excuse.

Acting under uncertainty requires energy, though. Mental fuel. And when that fuel runs out, everything changes.

That's next time: deciding when you're depleted. Because the hardest decisions in your life won't happen when you're rested and sharp. They'll happen at 10 PM after a brutal day, when someone needs an answer and you're running on empty.

Before You Go

You've got two choices right now.

Choice one: scroll to the next video. Let this become another thing you watched but didn't act on.

Choice two: pause for thirty seconds. Think about that decision. Set the deadline. Put it in your calendar before you leave this page.

Thirty seconds. That's the difference between insight and action.

If mindjacking is a new concept for you, I've got a full episode that breaks down how to spot when your thinking has been hijacked, whether by outside forces or by yourself. Watch is on YouTube.

For those who want to support the work and the team behind these episodes, you can become a paid subscriber on Substack.

One question for the comments: What decision are you finally going to stop researching and start making?

Your deadline begins now.

Sources

The Jam Study Iyengar, S. S., & Lepper, M. R. (2000). When choice is demotivating: Can one desire too much of a good thing? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(6), 995-1006. The study was conducted at Draeger's Market in Menlo Park, California.

The 40-70 Rule Attributed to General Colin Powell. The rule appears in "Quotations from Chairman Powell: A Leadership Primer" by Oren Harari (1996), based on Powell's My American Journey (1995). Powell served as a four-star general in the U.S. Army and as the 65th U.S. Secretary of State (2001-2005). The formula "P = 40 to 70" represents the probability of success based on percentage of information acquired.

The Two-Door Framework Bezos, J. (2015). Letter to Shareholders. Amazon.com, Inc. Annual Report. The framework distinguishes between "Type 1" decisions (one-way doors, irreversible) and "Type 2" decisions (two-way doors, reversible). Bezos elaborated on this in his 2016 shareholder letter, noting that organizations often mistakenly apply heavyweight Type 1 processes to reversible Type 2 decisions.